Birth Justice Tribunal Report Back

Released December 2024

“True resistance comes with people confronting pain…

and wanting to do something to change it.” - bell hooks

One in five pregnant people experiences discriminatory mistreatment during pregnancy and childbirth in the United States. Despite growing national attention on perinatal health inequities, too few options exist to seek- and find- accountability for these harms. Community-led strategies have emerged in response to this failure to account for this discrimination. This report amplifies these strategies, focusing in particular on those that emerged from the 2023 Birth Justice Tribunal.

On October 6th and December 1st, 2023, twenty-six brave families came forward with their experiences of violence and discrimination during the perinatal period at the 2023 Birth Justice Tribunal events in New York and Memphis. Honoring and believing in the power of centering people who have been directly impacted, this report weaves together their individual stories, anchoring its discrimination analysis in the voices and vision of people who have experienced obstetric violence and obstetric racism first-hand. The report concludes with community-led calls to action that we trust and believe hold the power to disrupt harm, and radically expand accountability for these harms.

Doula Is a Verb

At Elephant Circle, we like to say “Doula Is a Verb.” This simple sentence reflects a specific philosophy about our values and commitment to doula-work*.

Our philosophy includes 5 core principles:

Doula-work does not need to be professionalized in order to work or be valuable for the clients and communities doulas work alongside.

Doula-work in the U.S. today happens in the context of the broader perinatal health care system where inequity is built-in; doulas are only one strategy we have to equip people with tools and resources inside of these systems and spaces.

Doula-work is connected to a long history of care-work that has been systematically deprioritized and devalued inside of patriarchy and white supremacy.

Healthy communities have doulas.

Pregnant people are experts; they are best positioned to navigate their pregnancy, birth, and postpartum.

At Elephant Circle, we like to say “Doula Is a Verb.”

This simple sentence reflects a specific philosophy about our values and commitment to doula-work*.

Our philosophy includes 5 core principles:

Doula-work does not need to be professionalized in order to work or be valuable for the clients and communities doulas work alongside.

Doula-work in the U.S. today happens in the context of the broader perinatal health care system where inequity is built-in; doulas are only one strategy we have to equip people with tools and resources inside of these systems and spaces.

Doula-work is connected to a long history of care-work that has been systematically deprioritized and devalued inside of patriarchy and white supremacy.

Healthy communities have doulas.

Pregnant people are experts; they are best positioned to navigate their pregnancy, birth, and postpartum.

*Learn more about this term here: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/57126eff60b5e92c3a226a53/t/638f562c3ebfa36a53bf88de/1670338102604/FINAL+Advocating+for+Birthworkers+in+Colorado.pdf

1: Doula-work does not need to be professionalized in order to be effective

What do we mean by “professionalized”? Professionalization is a process that turns an activity into a distinct, standardized occupation (a “profession”). This process is often inspired by a desire to make more money from the activity. To make more money from the activity, people need to see it as an activity with a value that you can put a price tag on. To put a price on it, you have to be able to show exactly what it is, and distinguish it from what it is not. This usually requires distinguishing it from activities that aren’t in the market, like hobbies, religious callings, family duties, and relationship practices. You also have to put it into the market. Market rules can include fees, proof of credentials for the activity, and demonstration of standards.

People in your world probably have experiences with this. Maybe you have a family member who cuts hair but who couldn’t open a salon because they aren’t a licensed cosmetologist; or a friend who makes amazing food but runs into all kinds of roadblocks when they want to open a food truck. This process is not unique to doulas. As you think about it you can see how it is a process that involves a change in how people think about the activity, as well as a change in the economics of the activity, and the regulation of the activity. It deeply impacts who can do the activity and what the activity can be.

A stark example of professionalization in health care is midwifery. This process is still underway in the U.S. (and globally), and is well documented for those who want to learn more. Briefly, Midwifery is a human practice of support for pregnancy that has been happening across time and cultures. In the U.S. the effort to professionalize medicine, specifically obstetrics, included an effort to distinguish between the activities of obstetricians and the activities of midwives (even though many of the activities were the same). This process led to the criminalization and sidelining of midwifery, which reduced access to midwives, which then led to the professionalization of midwifery as a way to bring them back into the market and increase access. It’s a huge topic by itself, but if you’re talking or thinking about doula professionalization you should definitely study midwifery.

There are many lessons that can be learned from the history of midwifery professionalization and it’s clear that professionalization comes with pros and cons. Reasonable minds can come to different conclusions about those. But for us, one critical fact stands out: doula work does not need to be professionalized in order to work. The great outcomes policymakers tout, the intervention against inequities that doulas offer, and simply, the many benefits that flow from having a doula, exist because of the activities of doula-work. The benefits do not rely on (and may even be reduced by) doulas being a profession. In fact, the concept of “professionalism” has historically been weaponized against doulas, especially doulas of color – creating expectations that birthworkers adhere to standards of white supremacy culture masquerading as “professionalism”, and marginalizing those that do not assimilate. For people who care about getting more of these benefits to more people it is essential that you keep this fact in mind: doula-work is effective because “doula” is a verb.

2: Doula-work in the U.S. today happens in the context of the broader perinatal health care system where inequity is built-in

It turns out that the activities of doula-work, the action in the action-word, have been shown to improve outcomes. In studies, this activity has been defined as “one-to-one intrapartum support.” That having personal, individual, support helps people should be no surprise. The data bears out what we know logically and intuitively. Helping, helps! What may be less obvious is that one-to-one support is lacking in perinatal health care because it wasn’t built-in.

Why wasn’t it built-in and how do we know this? It wasn’t built in because the pregnant woman wasn’t the priority. The social and scientific significance of the pregnancy was more important and this significance varied by race and class. So, for example, certain obstetric procedures were developed on the bodies of enslaved Black women because those procedures could both support their value as property and increase the value of the obstetricians who could perform the procedures. But the support these women may need was not a consideration in the slightest. Even for privileged white women, the social and scientific significance of pregnancy was more important than their personal needs: the fact that they had a uterus dictated their purpose (pregnancy) and their position (secondary) and any support they may get was delivered through this lens.

Of course there are many perinatal health care providers today that see their pregnant clients as worthy of individual support. But they will have learned their trade from people who learned their trade from people who did not. They will practice in settings that were designed and built and bankrolled by people who did not see pregnant clients as worthy of individual support. This history is only 3 or 4 generations old. It is as present as your great-grandma’s recipes.

Doing the work of supporting a pregnant person one-on-one may help that person feel helped, and that may improve their lot. But doing the work of supporting a pregnant person one-on-one, even lots of them over and over, cannot change the shape of the system by itself. If support is an action that works, and we want more of it in the system, we’ve got to build it in. Doulas should not be the only people doing that action. Doula is a verb that everyone in the system could do - if it were built that way.

It is worth noting that midwifery incorporates the value of the pregnant person more effectively than other models (as illustrated by various surveys and data) and part of the inequity built-in to the status-quo comes from the marginalization of midwives. Incorporating doulas into the system cannot resolve this inequity. A system that truly addresses perinatal inequities includes midwives.

3. Doula-work is connected to a long history of care-work that has been systematically deprioritized and devalued

Work is part of the human condition. Every culture across time has had a system for organizing work. One of the ways work has been organized is by separating the “domestic” work from “real” work.

Work that drives markets has been prioritized in the U.S. and has relied on “domestic work” being available and undervalued. Work involving the care of children, elders, people with disabilities, pregnant and postpartum people, and homes, has been considered “domestic work” and associated with women and lower-classes. Today, the majority of “domestic work” as a profession, is done by women of color (over 90% of domestic workers are women and Black, Hispanic and Asian American/Pacific Islander women are vastly overrepresented as a proportion), and “unpaid family work” like care of dependents and households is still performed mostly by women.

At Elephant Circle we are aware that work is not neutral, that work is about power. So the issue of doula-work has to be considered in the context of the organization of work in society more broadly. We see doula-work, that action-verb of one-on-one care and support, as part of the broad umbrella of care-work. Ai-jen-Poo, Director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, calls care-work, “the work that makes all other work possible.” We need to think about what work doula-work makes possible.

Care-work has been marginalized socially, culturally and through explicit policies. For example, when other workers got protections through the Fair Labor Standards Act one hundred years ago, those who performed care-work were explicitly left out. This had the effect of maintaining racialized and gendered inequality. The inequality was the point.

Because inequality was built in, we need to think about what inequalities the organization of doula-work maintains, and how we can organize doula-work to dismantle inequities.

4. Healthy communities have doulas.

Along with the idea that doulas can address inequities in perinatal outcomes is the idea that doulas can bring culturally congruent care. In this vision, doulas reflect the communities they are in and are able to step in to care for the people in their community who need them, and that money isn’t a barrier to that care for the people who need it or the people giving. We love this vision!

But we keep in mind that the process of culturally congruent care is one that happens spontaneously in communities. Culturally congruent care isn’t “out there.” People care for each other as part of social-mammalian systems. Social-mammalian systems are ordered for in-group care. We already know how to do this! It’s just that things get in the way. We are concerned that by focusing on doulas as the solution we lose sight of where the problem actually lies. It isn’t that we lack the capacity or awareness to care, it is that culturally congruent care has been disrupted.

Some of the things that disrupt our social-mammalian instincts to care for each other are 1) the marginalization of care-work (see above), 2) socially constructed timelines and calendars that work against the rhythm of the perinatal period, 3) extractive economic policies, 4) organizing health systems around disease instead of wellness, and 5) oppression that defines some people as unworthy of care.

This is one reason why the image of the elephant circle is so important to us. It reminds us that we too are mammals. We already have a blueprint for this. We are part of the ecology. By looking to doulas as the solution we should be cautious not to take our eye off the problem. Setting up structures to support culturally competent doula care doesn’t guarantee that the structural problems are fixed. In fact, a surface solution could even distract from the problem in the short term. We want to see systems that are built for our mammalian circles, and protect against things that disrupt us.

5. The pregnant person is best positioned to navigate their pregnancy, birth, and postpartum.

Along those lines, one of the inequities built-in to the system, as we have discussed, is how the pregnant person is not the priority. To the extent that “doula” is the verb, the pregnant person is the noun, the subject of the sentence.

We don’t want to lose sight of the pregnant person. As the studies and our intuition show, doula-work can make a difference. But if the pregnant person’s life circumstances are dire, that support can only go so far. If the pregnant person is still not a priority in the system, that support can only go so far. Since doula-work is some of the only work in the current perinatal care system dedicated exclusively to the pregnant person, it is a powerful tool for reorienting the system. But it’s not the only tool and maybe not even the best one.

Doula-care can improve outcomes. But strong, healthy pregnant people who are respected, prioritized, and resourced, also improve outcomes. Keeping the focus on pregnant people themselves is key.

In conclusion, Doula is a Verb is how we practice doulaing, how we organize doulas, and a political-orientation to the role of doulas in caring for and supporting people across the perinatal period. It’s a practice of principles that reorient the perinatal system so that care is a top function and priority. Care isn’t just an intention you hold in your heart, it’s a way of taking action that anyone and everyone can do. This practice is also a way of resisting and reversing built-in inequities, so that women, people of color, and gender nonconforming birthing people are healthy and free.

Provider Discrimination in Medicaid Reimbursement is Unlawful

Read our brief “Legal Bases for Medicaid Reimbursement for Direct Entry Midwives in Colorado” here.

On July 20, 2023 we submitted this brief “Legal Bases for Medicaid Reimbursement for Direct Entry Midwives in Colorado” to HCPF and other allies and stakeholders to address HCPF’s failure to credential or reimburse Colorado Direct Entry Midwives.

This thread illustrates the denial and run-around of one particular midwife who sought to be enrolled as a Medicaid provider.

Federal Civil Rights Investigations - An Opportunity for Accountability

Highlighted in this story from the LA Times, this post talks about the value of making complaints of perinatal harm to the Office for Civil Rights.

This article from the LA Times about a federal civil rights investigation into the pregnancy-related death of Kira Johnson illustrates the potential for the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) to bring much needed systemic accountability for birth inequities, obstetric racism and obstetric violence.

Elephant Circle has been working on developing this pathways for years, having first met with leaders at the OCR in 2021. We now have a process in place to help people file complaints with the office - learn more here and share widely!

We also wrote a comprehensive brief on the issue, Mobilizing the Office for Civil Rights’ Authority to Address Obstetric Violence and Obstetric Racism, which we delivered to the Office for Civil Rights in 2022. Follow-up conversations we have had with the office in 2023 confirms that this is a tractable pathway. We encourage anyone who has experienced obstetric racism, obstetric violence, or inequities during the perinatal period to file a report.

Cedars-Sinai faces federal civil rights investigation over treatment of Black mothers

BY MARISSA EVANS STAFF WRITER

JULY 11, 2023 5 AM PT

Cedars-Sinai Medical Center is facing a federal civil rights investigation over how the Los Angeles hospital treats Black women who give birth there, an official with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services confirmed.

The investigation comes after allegations of racism and discrimination emerged in the years after the death of Kira Dixon Johnson.

Johnson went to Cedars-Sinai in April 2016 to deliver her second son by cesarean section but died hours later after hemorrhaging blood. News of the incident spread over social media and led to her husband, Charles Johnson IV, filing lawsuits against the hospital over her death.

The Times obtained a copy of a letter the federal agency sent to Charles Johnson in March indicating that it was aware of the allegations involving the hospital’s level of care for Black women.

The Office of Civil Rights “has been made aware of concerns regarding the standard of care provided to Black women in the care of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center,” the letter said. “Specifically, OCR is aware of allegations that Black women are provided a standard of care below what is provided to other women who are not Black when receiving health care services related to labor and delivery.”

The letter noted that based on the allegations and the fact that Cedars-Sinai receives federal funding, the agency is reviewing whether the hospital is complying with federal civil rights laws.

Melanie Fontes Rainer, director of HHS’ Office of Civil Rights, confirmed the agency’s investigation in an emailed statement.

“Maternal health is a priority for the Biden-Harris Administration and one in which the HHS Office for Civil Rights is working on around the country to ensure equity and equality in health care,” Fontes Rainer said. “To protect the integrity of this ongoing investigation we have no further comment.”

Landscape Analysis

Elephant Circle is writing a community-based landscape analysis, learn more about what we are thinking and how the process is unfolding here.

In the past few years interest and awareness in birth justice has grown tremendously, as has philanthropic support and impact investing. There is no doubt that increased attention and investment is sorely needed. However, without an understanding of what the landscape includes, who is there, doing what, and why, that increased attention and investment could be ineffective or even harmful. This reminds us of the way a sudden downpour impacts the land in the dry west where Elephant Circle is based. Mapping and planning can help maximize the benefit of much needed water, while mitigating the harms. We are working to make sense of what’s happening in our landscape so that people can plan and strategize. To receive outreach and updates add your name here!

A view of state infrastructure destroyed by heavy rains, with some areas receiving as much as 18 inches in a 24-hour period in Boulder, Colo., Sept. 14, 2013. (U.S. Army photo by Staff Sgt. Wallace Bonner/Released)

Plan for a Landscape Analysis for the Birth Justice Movement

In response to poor outcomes in maternal health, persistent experiences of structural racism and gender-based violence, poor quality and disrespectful care, local communities have generated a movement for “birth justice” to create perinatal health services, support systems, and policies that address and improve these conditions. Understanding the response mechanisms communities are using to address these problems, and the ecology, is key to understanding birth justice and how to maximize opportunities for change.

The goal of the project is to provide a reproductive justice framework for understanding who is doing what, and why, for people in the perinatal period, in the U.S.

A deep understanding of community led strategies through a national birth justice landscape analysis will allow birthworkers, activists, researchers, donors, and policymakers to identify key strategies for collective impact, enable tangible improvements, and scale up. Elephant circle is uniquely positioned to conduct the landscape analysis with a team of researchers, activists and change makers who are deeply connected within the birth justice movement. Through a community led qualitative landscape analysis over six months we will:

Define the birth justice movement and why and how it is both part of, yet distinct from the reproductive justice movement.

Describe the networks and alliances within the birth justice movement. and map the services and strategies offered for people in the perinatal period, in order to create a picture of the existing change-infrastructure.

Describe the funding needs of the birth justice movement and how funding for various services and strategies may impact it.

Caution against funding strategies that could be detrimental to the movement and its participants.

Recommend a strategic approach for the larger maternal public health/early childhood health landscape to work with the birth justice movement and participate in improving outcomes.

The process will include pathways for individuals, invited organizations, and sponsors to engage and inform the report.

Individuals can participate in community meetings, interviews and surveys. Some individuals will also be invited to be reviewers.

Organizational partners host community meetings or invite their networks, recommended interviewees, participate in and share surveys, and provide reviews. Organizational partners are invited or nominated by other partners.

Sponsors make a financial commitment to support the work of the report. Funders that contribute at least $10,000 will be recognized. Organizations that sponsor at a rate that is commensurate with their budget will also be recognized. If you’re interested in being a sponsor contact Indra at indra@elephantcircle.org

To receive outreach about community meetings and interview opportunities, or updates about our progress, add your name here! Check our events page for more about the Community Meetings.

Thank you to Orchid Capital Collective for encouraging us to take this leap! And thank you to Perigee Fund and Ms. Foundation for their support of this effort.

Policy and Demographic Considerations for LGBTQIA Families and Midwives

This write-up provides an initial and novel analysis of data about midwifery integration and LGBTQ equality.

Midwives who either are themselves lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, intersex, two spirit or other aligned identities (LGBTQI2S+) or want to serve the LGBTQI2S+ community have to consider both the policy environment for the practice of midwifery and the policy environment for LGBTQI2S+people. This write-up provides an initial and novel analysis of data about midwifery integration and LGBTQI2S+ equality. There are some great tools available to address these issues. We hope to bring them all together for the first time here.

The Birth Place Lab created an interactive map based on their paper “Mapping integration of midwives across the United States: Impact on access, equity, and outcomes.” The maps can be accessed at: https://www.birthplacelab.org/maps/

Using the “Integration” tab on the map, you can quickly get a sense of where midwifery is most integrated and where it is least integrated. There are four levels of integration on the map. You can also click on each state to get some more details or to see how integration relates to birth outcomes. For even more information they have created a “report card” for each state. The report cards include five components of midwifery integration for the CNM, CPM and CM credentials including whether that credential is licensed, covered by Medicaid, authorized to write prescriptions, has easy access to physician referral, and no restrictions on site of practice.

Integration is “scored” on a scale of 1-100. Even the state with the best midwifery integration score (Washington) has room for improvement (they have a score of 61 out of 100). But even the lower scoring states (like North Carolina with 17 out of 100) are worth taking a closer look at to learn for example, that the percent of births attended by midwives there is higher than the national average (13.4% versus 10.3%) and higher than other states with more midwifery integration like Missouri which scores 39 out of 100 but where midwives attend only 4.4% of births. Seven states in the West and Northwest are in the highest category of integration, with five in the Northeast and one in the Midwest. But there are thirteen states in the second-highest range spread across the country.

There is also a “Density” tab on the map, that illustrates where there are more and less midwives in the country which can be further distinguished by CNM/CM versus CPM. Right below that is the “Access to Place of Birth” tab that illustrates access based on the relative amount of community birth in each state, which can then be distinguished based on home or birth center, and CNM/CM and all other midwives. Together, the “Density” tab and the “Access to Place of Birth” tabs provide a view of where midwives are across the country.

There are twenty states that meet the two highest levels of midwife-density, but only four of those have the highest levels, Vermont, Oregon, Maine and Alaska. Of those, Vermont, Oregon and Maine have high rates of CPMs, while Alaska has higher CNM density. Of course, more midwives are needed everywhere. We don’t yet have demographic data about how many midwives are LGBTQI2S+ or how they are distributed throughout the country. There is also a tab that illustrates the percent of “Black Births” by state, but not the race of the midwives, and other racial categories are not mapped for percent of births of midwives.

For information about the LGBTQI2S+ population State-by-State, the Williams Institute has done extensive demographic research and has a map which can be accessed at: https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/visualization/lgbt-stats/?topic=LGBT#density These are complex demographics to calculate, not to mention complex categories to define. Notably, the Williams Institute categorizes people demographically as “LGBT” whereas The Equality Maps uses “LGBTQ.”

Based on the Williams Institute data, 4.5% of the adult population in the United States is LGBT, 29% are raising children, and 25% have income of less than $24k per year (another myth the Williams Institute has tackled is that LGBT people are more affluent than their heterosexual counterparts: they are not). This data project includes the “LGBT People Rankings” where the percentage of LGBT people who are raising children are ranked for twenty states. The highest, is Idaho where 44% of LGBT people are raising children, followed by Utah, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Delaware and Mississippi.

This information can be combined with the Equality Maps created by the Movement Advancement Project (MAP) which can be accessed at: http://www.lgbtmap.org/equality-maps

Together, these three maps provide a view of how midwifery integration lines up with the policy climate for LGBTQ people and families.

The Equality Maps indicate “policy tallies” of all the states. State scores are ranked in five gradations from “High” to “Negative.” The policy tally combines the Sexual Orientation Policy Tally and the Gender Identity Policy Tally. You can also look at the map based on the Sexual Orientation Policy Tally alone or on the Gender Identity Tally alone. Overall, 46% of LGBTQ people are living in states with “High” or “Medium” scores, and 45% of LGBTQ people are living in states with “Negative” or “Low” scores.

The policy tallies come from MAP's tracking of dozens of LGBTQ-related laws. Those laws fall into seven categories: Relationship and Parental Recognition, Nondiscrimination, Religious Exemptions, LGBTQ Youth, Health Care, Criminal Justice, Identity Documents (it’s possible to look more deeply into each of these types of laws in their methodology information). The states aren’t ranked from highest to lowest like they are for the midwifery integration scores, but you can look at the data in a table instead of as a map.

In the state profile you can see both tallies, plus the percentage of the state’s population that is LGBTQ and the percent of LGBTQ people in the state raising children. Population numbers are based on estimates created by demographic researchers so there is some interpretation involved (which explains why the percentages in this map vary a bit from the percentages in the Williams Institute maps referenced below). The numbers are not broken down by gender identity, sex,or race, and it’s not easy to determine how many of those raising children gave birth to those children.

By way of example, Washington is in the “medium” category overall (and “high” for Gender Identity) and 5.2% of the adult population is LGBTQ, with 29% of those folks raising children. North Carolina is in the “low” category overall (and “negative” for Gender Identity), and 4% of the adult population there is LGBTQ, with 26% of them raising children. Missouri is also in the “low” category overall, and have a lower percent of the adult population who identify as LGBTQ (3.8%), but even more of them are raising children (30%).

One of the most interesting discoveries from the demographic data about LGBTQ people is how many LGBTQ families are in rural areas and areas with negative laws. For example, Kansas, which is near the bottom in terms of midwifery integration, and is also near the bottom in terms of equality tallies, nonetheless is a place where 40% of the LGBTQ population is raising children. This is something to consider for LGBTQ midwives or midwives especially interested in serving the LGBTQ population.

We analyzed midwifery integration scores, midwifery density, Equality Tallies, and LGBT population (both the percent of the overall population that is LGBT and the percent of the LGBT population raising children for the top 20 States).

Three states stood out for their high scores (top twenty) in all five categories: Delaware, New Hampshire, and New Mexico. That means in these three states, midwifery integration is among the highest in the country, overall equality tallies are among the highest, the percentage of the population that is LGBT is among the highest, and the percentage of LGBT people raising children is among the highest.

Five states were in the top twenty in four out of five of these categories: Hawaii, New York, Oregon, Vermont and Washington. In these states there are several things going for midwives and LGBT folks. Hawaii had a lower midwifery integration score that set it apart. The other four had a slightly smaller percentage of the LGBT population raising kids.

Seven states had three out of five scores in the top twenty: California, Colorado, Maine, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Utah and Wisconsin. Utah and Wisconsin had lower Equality Tallies which set them apart in this group, but sizable proportions of the LGBT population raising kids and decent midwifery density. In contrast, Maine and Massachusetts didn’t make the top twenty in terms of percent of the LGBT population raising kids - but their rates were still high. Colorado wasn’t quite as strong in midwifery integration but had more midwifery density, while California lacked midwifery density but had a decent integration score (again, keeping in mind that 61 was a high score out of 100, so all top 20 states have room for improvement).

Seven states are worth looking twice at despite some problematic scores because they present an opportunity in some way: Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana, Maryland, Minnesota, Nebraska, Nevada. For example, Arkansas has a -.5 Equality Score, but 36% of the LGBT population there is raising kids, and the midwifery integration score is in the middle of the pack. Idaho, mentioned above, has the highest percent of the LGBT population raising kids, a high integration score, and a low equality tally, but one that is not “negative” (the lowest level).

Six states have the unfortunate distinction of having high proportions of LGBT families, combined with “negative” Equality Tallies, and fair-to-good midwifery integration: Mississippi, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, and Texas. These states might have something to offer midwives, but should also be scrutinized carefully for a realistic view of how dangerous the climate could be for LGBT people.

As far as we know midwifery integration and LGBTQI2S+ equality have never been analyzed together, and there is room for more analysis across the board. From analyzing midwifery density by more detailed demographics (like the race and LGBTQI2S+ identity of midwives), to analyzing how the children who are being raised by LGBTQI2S+ folks were born, and the demographics of those families by race, and gender. Not to mention surveying the experiences of LGBTQI2S+ families during the perinatal period (check out Birth Includes Us).

Despite the relatively small numbers in the population of midwives and the populations of LGBTQI2S+ people, this is important work from an equity perspective. As efforts to increase the midwifery workforce continue, so do efforts to ensure that workforce is diverse and capable of meeting the needs of the community including people of color, LGBTQI2S+ people, and LGBTQI2S+ people of color.

This was originally written in February of 2020. Some data may have changed.

We Must Oppose Inhumane and Unjust Prosecutions of People in the Perinatal Period

SB23-1187 lends support to these efforts, along with a letter asking a Colorado DA to drop charges against a postpartum defendant.

This legislative session Elephant Circle, along with a coalition of organizations* worked to pass a law that would protect the perinatal period at all stages of the criminal legal process.

Here is a fact sheet about the bill, HB23-1187, and here it is on the Colorado Legislature website. Elephant Circle has been involved in advocating for incarcerated people who are pregnant or postpartum since 2010 when we helped pass a law to prohibit use of shackles on pregnant and laboring people. Since then we have had groups at Denver Women’s Correctional Facility for many years, and collected stories from people who experienced incarceration during the perinatal period (thanks to the storytellers and support from Colorado Equity Compass).

We have also tracked cases across the country of people being charged for crimes specifically related to the perinatal period and understand the unique vulnerability of people facing such circumstances, including an increased exposure to blame (see for example Blaming Mothers by Linda Fentiman, who testified in support of SB23-1187).

Unfortunately, the need for policy change and advocacy in this area has been confirmed by Arapahoe County, Colorado’s prosecution of two parents for the death of their one-day-old newborn. No, there is not any evidence to suggest they caused their newborn’s death, and we are calling on the District Attorney prosecuting this Colorado case to drop the charges.

When such a young baby dies an investigation is inevitable, and such investigations are ripe for all of the emotions, stigma, and bias surrounding pregnancy, birth, and early parenting. Someone will certainly be blamed; mothers and midwives are the most common. When this happens, often, normal and appropriate things that mothers and midwives do are recast as criminal.

For example, in one case we are familiar with a woman who had been using drugs and did not know she was pregnant, went to the hospital complaining of abdominal pain. Still not knowing she was pregnant, which had also not yet been diagnosed by hospital staff, she went to the bathroom (within the hospital) where she proceeded to give birth while sitting on the toilet.

The prosecution recast the fact that she was sitting on the toilet to birth the baby as evidence of this mother’s criminality, as if it suggested malice or indifference: it does not. In fact, birthing stools which have been used throughout history, look quite like toilets, because it is very supportive and appropriate shape to facilitate birth.

Compounding the problem of bias-prone investigation is the problem that people tend to think if someone is punished it must be for a reason, they must deserve it. This can further isolate and stigmatize the person who is being blamed, even when that blame is unearned. The criminal legal system should guard against such dynamics through due process, but in these highly charged cases the due process that exists is inadequate or set aside, overridden by emotion, bias and stigma that can lead prosecutors to cut corners and ignore or withhold exculpatory evidence.

Take for example this case from South Carolina, where a mother was charged with killing her newborn through breastmilk that contained high levels of morphine. Experts contend that it would be extremely unlikely, if not physiologically impossible to transmit enough morphine through breastmilk to harm a child (without an innate genetic condition that impacts metabolism).

But since the breastmilk was not tested for levels of morphine, and other modes of transmission of morphine were not investigated, critical information was simply unavailable. Similarly, in this recent Arapahoe County case, the formula was not tested, the prosecution delayed sharing the autopsy report which is supportive of the defense, and the prosecution is still withholding potentially exculpatory evidence (of the parents’ consistent negative drugs tests, among other things). This underscores the implicit bias at play; the assumption that someone is to blame shuts down inquiry and curiosity.

We need strong policies that guard against these weaknesses, and better protect due process and human rights. SB23-1187 aims to reinforce the value of protecting this unique timeframe for both the pregnant/postpartum person and the newborn. It aims to provide prosecutors, defense attorneys and judges with extra reason to consider and reconsider the facts in any criminal case involving someone who is pregnant or within one year of the end of a pregnancy, and be very reluctant to incarcerate during this time.

We are sad that the need for this policy was confirmed so soon after the law passed, but appreciate the motivation to push forward with this work and ensure that the law is enacted as intended.

Supporting Organizations:

Elephant Circle, Soul 2 Soul Sisters, ACLU of Colorado, Children’s Campaign, Colorado Center on Law and Policy, Colorado Consumer Health Initiative, Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition, COLOR, Healthier Colorado, New Era Colorado, Office of Respondent Parents’ Counsel, Planned Parenthood of Rocky Mountain, ProgressNow, Reimagining Policing Taskforce, Together Colorado, Women’s Foundation of Colorado, Young Invincibles,

Payment and Equity for Birthworkers

This blog post include fact sheets related to birthworker reimbursement in Colorado, as well as context and framing of perinatal care work.

It is widely understood that there is a crisis in perinatal care in the United States. (See Maternity Care in the United States: We Can - and Must - Do Better from Nat’l Partnership for Women and Families, for context).

It is not just that something isn’t working in the interactions between providers and patients (though that is part of the problem as indicated in measures like Giving Voice to Mothers study).

The structure of perinatal care is also part of the problem. For example, it is built in to the structure that most providers of perinatal care are physicians and most births in the U.S. occur in hospitals (see for example this video from Vox and ProPublica and this report from the Commonwealth Fund comparing the U.S. to ten comparable countries).

Fixing the problem requires changing the structure. One part of the structure is how the money flows. This is why it is so important whether, how, and how-much birthworkers are paid.

This is part of why the 2021 Birth Equity Bills included a requirement that both public and private insurance in Colorado reimburse providers in a manner that:

promotes high-quality, cost-effective, and evidence-based care

promotes high-value evidence-based payment models

prevents risk in subsequent pregnancies

These requirements are now law in Colorado, see C.R.S § 10-16-104 and § 25.5-4-425, and are aimed at addressing both the lack of evidence-basis for much of what happens in perinatal care, and the existence of strong data supporting integration of midwives and doulas. See, for example, Maternity Care in the United States: We Can - and Must - Do Better from Nat’l Partnership for Women and Families and Expanding the Perinatal Workforce through Medicaid Coverage of Doula and Midwifery Services, from the National Academy for State Health Policy..

Despite these laws, inequities continue and more work needs to be done to realize these goals.

These Fact Sheets are also useful for understanding what is happening in Colorado:

Elephant Circle’s Statement on the Governor’s Budget Request for Reimbursement of Doulas

Barriers to Reimbursement for CPMs and Freestanding Birth Centers in Colorado

But the problem isn’t just about the healthcare system, it is also about a system-wide failure to value, plan for, and invest in care-work (see this interview with the Culture Change Directors at Caring Across Generations and the National Domestic Workers Alliance, see also “Care Can’t Wait,” about creating a comprehensive care infrastructure).

We lack the infrastructure to support the care humans need, including in the perinatal period. Birthworkers are part of the solution because of how care is woven into the work. But if the system they work in doesn’t value care then their existence in the system won’t ensure care matters (and they may feel uncared-for as well).

We want to help transform the system to one that values care and invests in it like the infrastructure that it is.

For additional context:

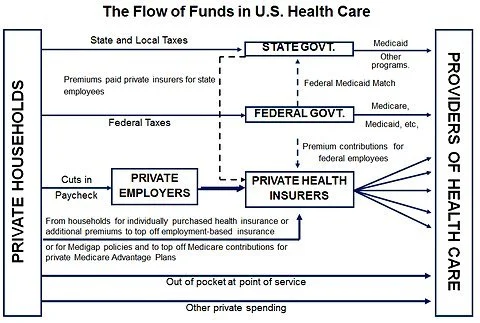

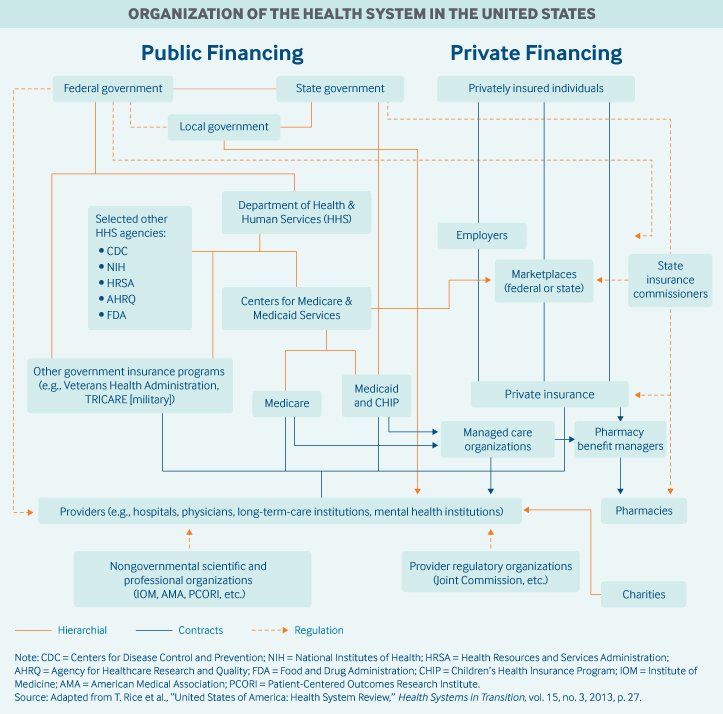

Paying nonclinical birthworkers as part of the healthcare system isn’t simple since the way payments work in the system isn’t simple. To get a sense of the complexity of payment in the U.S. healthcare system, these two charts illustrate how the money flows. This is also how it flows in the perinatal care system.

Part of the reason birthworkers, like doulas, are helpful is because this system is not good at ease, continuity, or flow for the patient - it’s organized around other interests as illustrated in these graphics - so having someone help navigate that chaos can be helpful to the patient.

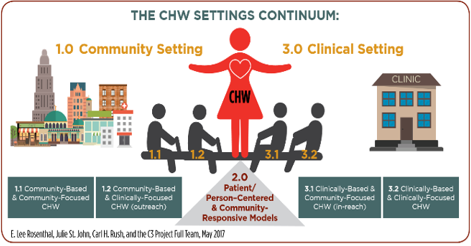

Some other nonclinical providers that have been used in this way is Community Health Workers. (See this article to get a sense of how community health workers are utilized and considered in the system, and this article about sustainable financing for them). The following graphic from the article is illustrative.

Effectively Partnering with Communities in Research to Improve Maternal Health Outcomes

“Effectively Partnering with Communities in Research to Improve Maternal Health Outcomes and Reduce Disparities: Using Research to Create Community-Centered Policy” held on March 10, 2022. Hosted by Maternal Health Coordinating Committee (MHCC) of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

the 508-compliant webinar recording is now available for public viewing at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=en47IZa_fOA

Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act Webinar

Elephant Circle participated in the creation and presentation of this webinar about the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act and the Comprehensive Addiction Recovery Act for the New York State Department of Health. Much of the information presented is relevant for a wider audience, including anyone who is a "mandatory reporter" under state law. The presentation contextualizes the family regulation system and its impact on families including people who use drugs during pregnancy. Click on this link to register to access the recording.

Birth Equity Laws - Implementation!

The bills have become law. Now to the work of implementation…

As discussed in the Birth Equity Bill Package blog post, our ambitious set of legislation has been signed into law. And with it - lots of implementation work begins.

To facilitate that work we have been hosting various community meetings. Check out our Events Page for the latest meetings you can join! Consider reading the above blog post to get a sense of what the bill process was like and what was in the bills.

And we know this is just the beginning, if you have additional ideas for policy solutions, please share them here: bit.ly/birthequityideas

We also have recordings of these introductory meetings to help people get oriented to participation.

September 28, Support for Incarcerated Parents Work Group

September 30, Payment Work Group, access code: DoBE2021!

October 1, Implementation Steering Committee, access code: DoBE2021!

November 2, Civil Rights Work Group, access code DoBE2021!

November 4, Provider and Facility Work Group, access code DoBE2021!

You can also learn about some foundations of our work in this places:

Read our Policy Platform, which Includes a link to our Blueprint for Birth Justice

And this interview with people involved in the bill process provides a glimpse of how we work.

Sex is Not Binary

Some resources to help you navigate the fact that neither gender nor sex are binary.

We are so often faced with misinformation about sex, namely that it is binary, that we are posting here some of our favorite resources on that topic.

This is a RadioLab episode called Gonads: X&Y which is about how sex is more than chromosomes and much more complex that XX or XY.

This is a Scientific American articled called Sex Redefined: The Idea of 2 Sexes Is Overly Simplistic, and the title certainly sums it up well. For a more technical approach consider this Nature article, Genetic Mechanisms of Sex Determination.

This video from Human Rights Watch and InterAct illustrates the conditions intersex people and the parents who advocate for them experience in terms of pressure to conform, even via surgery, to binary notions of sex.

Here is National Geographic’s Gender Revolution Issue - some of it is behind a paywall, but the Discussion guide is not.

We also recommend The Gender Wheel by Maya Gonzalez and her children’s book by that name.

All of these only scratch the surface, there are a lot of great materials out there for those willing to explore.

For those concerned that there is a “trans agenda” or that women are being erased and have to be defended by undermining transgender and intersex people, well… It is not clear that there is anything we could say. But - you might be interested in the connections between anti-trans feminism and the Christian right which is described in this article, A Room Of Their Own: How Anti-Trans Feminists Are Complicit in Christian Right Anti-Trans Advocacy.

Tactics for Transformation in Birth Justice

This blog post illustrates the targets for whom calling-in is a good strategy for transformation, and encourages thoughtfulness and strategy around targets and tactics.

What is a tactic?

A tactic is “an action or strategy carefully planned to achieve a specific end.” (Websters) The most important thing to know about tactics is that there are many. People often have a go-to tactic that they always think of when confronting obstacles or trying to persuade targets. It’s fine to have favorite tactics, but it is unnecessarily limiting to only use one or two.

The whole point of being tactical is tailoring your approach to a specific goal. Not every situation calls for the same tactic. As you strive to increase your effectiveness you will want to increase your set of tactics. At Elephant Circle we value being multidisciplinary because it means we have more tactics to choose from which can help us choose more effective and efficient tactics. We often use tactics from the fields of education, art, science, the law, and community organizing.

A diversity of tactics is needed because each situation is different, and all tactics might not be available for or effective with each target. For example, many of the harms people experience during birth, from force or coercion to lack of access to midwives, are not easily remedied through traditional means of complaint/resolution or lawsuit/judgment so we have to get creative to effectively confront these things.

What is a target?

The book Politics the Wellstone Way: How to Elect Progressive Candidates and Win on Issues describes a primary target as “the individuals or groups that actually make a decision about your issue.” And secondary targets are “the individuals are groups that influence the primary targets.” Regardless of the issue at hand it is worth thinking in strategic terms about who is responsible for what, and who holds the levers of power. It doesn’t have to be a legislative or governmental issue to warrant strategy. For example, even racism, which is ubiquitous, can be strategically addressed. Tools like the the lens of systemic oppression provide a way of thinking strategically about problems like racism (and the tool works for other forms of oppression as well).

Once you know the targets you can map their relationships to identify opportunities for influence and change. The process called power-mapping can be a liberating and empowering way to identify and strategize around power dynamics. Check out this great little video on power mapping by former Colorado State Senator, Jessie Ulibarri.

Calling out and calling in

Calling out and calling in are tactics suited to different targets depending on the overall goal. Much has been written about calling out versus calling in. We strongly recommend diving into the great writing on that subject, it’s Googleable and a quick search pulls up several articles including this one by Birth Rights Bar Association Board Member Jenn Mahan. This feature explores Loretta Ross’ efforts to redirect calling out (which can be an overused tactic lacking in strategic value) to calling in (which has movement building and transformational utility).

We are also inspired by the work of survivors who have developed transformative justice strategies that respond to harm and violence without relying on policing, punishment, or incarceration. Policing, punishment and incarceration have negative effects that ripple through society and often negatively impact the same communities we are trying to protect. For more about this, we recommend the book Beyond Survival: Strategies and Stories from the Transformative Justice Movement. And we are delighted that one of Elephant Circle’s early collaborators, Elisabeth Long, has an essay published in it! We also recommend this series of videos:

· What Does Justice Look Like for Survivors?

· What is Transformative Justice?

· How to Support Harm Doers in Being Accountable?

Collectively these resources illustrate a range of tactics beyond calling out that can be used in a range of scenarios and on a range of targets.

Tactics for Transformation in Birth Justice

Strategy and creativity are needed to bring about transformation and pave the way for birth justice. Birth justice can be overwhelming because there is not just one target, and since racism is everywhere it can seem like anyone and everyone is a potential threat/target at all times. Thinking through tactics and targets is an important step because there are people and organizations with more and less power, and those positions can be revealed and even mapped.

Being strategic about power dynamics is critical to transformation. If you remove a threat without transforming it, another threat will simply fill the void created by removal of the first, like whack-a-mole.

At Elephant Circle we envision a world where every pregnant person has a circle of support and protection during the entire perinatal period. Barriers to that vision are our foes. But – every foe is not an equal target. Someone’s abusive family member might be a big barrier to their circle of support, but as a matter of strategy, we do not aim to eliminate every abusive family member. Instead, we set our sights on people and organizations that have levers to power that influence many more pregnant people at once.

People often aim their firepower at lower-level targets with limited influence, often because those targets are more obvious or accessible (and because of how the human mind perceives threats). Sometimes people aim their firepower at targets who are even on their side. The graphic below illustrates this. The target in red is a target with little power, who leans toward supporting our goals. The target in green has more power and leans toward opposing our goals.

It is possible that both the red and the green target need to be addressed in some way – but probably not with the same tactic. For targets who are near our same level of power, or below, and who are in the supportive portion of the map, we prefer tactics like calling-in. Tactics that preserve and strengthen relationships and create pathways for increased understanding. The following graphic illustrates the range of targets suited to calling-in when you are at the yellow star level on the map.

Other targets on the map may warrant other tactics; tactics individualized for the target and the goal. For example, even the green target may not be suited to a tactic of elimination (punishment, removal), but might be more suited to persuasion that moves them over onto the support side of the map. As the transformative justice movement illustrates, even harm-doers can be called-in, instead of being punished, policed or incarcerated.

Another part of the analysis is to consider: what tactics are generally effective on this type of target? Are there available pathways of redress for this harm? For some harms, the are no effective pathways for redress. Civil disobedience is a good example of a tactic designed for a situation where there are no effective pathways for redress of harms. Often using such a tactic is a strategy in pursuit of more formal pathways of redress, like how the sit-ins eventually led to the Civil Rights Act.

In some scenarios, multiple different tactics are used on the same target successively in increasing intensity, or simultaneously by different strategists. For this approach it is important to think about the whole ecology, what other strategists are out there, and how can your actions compliment, amplify or support theirs. Also, how and with what intensity do your tactics need to be used for the best effect?

Again, when it comes to birth justice, creativity is often required because there are no good formal mechanisms for redress of harms. But not every situation is the same. One of the most common disputes among people, well-developed in our legal system, is the dispute over contracts and money: who paid what to whom and what number was agreed to? For this type of harm there are well-worn pathways that many people can use, even people without a lot of money or time. Consider using a well-worn pathway when it is available and generally effective, like small claims court instead of social-media shaming.

This graphic from the Birth Rights publication illustrates a range of tactics or ways to say that “what happened to me was not okay.” In the narrative of this section the pros and cons of each tactic is discussed. We recommend doing a pro-con analysis before implementing your tactics (and of course we recommend reading the Birth Rights resource available here in English and Spanish).

Because each situation is different, and each person or group will have different values and priorities, having a diversity of tactics to choose from is helpful. No matter how many tactics you know about or use, there are always new things to learn. To expand your thinking about practices that constitute tactics, we also recommend adreienne maree brown’s books Emergent Strategy and Pleasure Activism.

Like brown, we also think of it ecologically: what kind of environment do our tactics create for all the beings and ideas we want to protect and see thrive? A slash-and-burn tactic might be effective in the short term, but could have undesirable long term effects (as illustrated so many times throughout history). As a result we practice being thoughtful, considerate and strategic about both targets and tactics, in order to maximize the possibility for transformation and minimize the possibility of creating power vacuums that will be filled by more of the status quo.

Lack of Information is a Weapon of Oppression

As Demetra Seriki said so emphatically to 9News, "Being heard is a life-saving conversation...." This blog post ties the failure of providers to listen, to the willful ignorance of policymakers. In both arenas, being heard is life-saving.

If you are in a position to influence or block policy solutions and do not have the information you need, cede your power to someone who does. Unfortunately, this essay arises from our experience with professionals who have insisted that they cannot support a particular policy solution, or even need to block policy change, due to a lack of information. This is unacceptable. It is especially unacceptable when the policy solutions are being advanced by people who are directly impacted. There will always be someone whose life experience required them to find, understand, process and take a stand based on the available information, and those life experiences make them well-suited to policy change. Those life experiences are information that can and should be translated into policy solutions.

Lacking information is unacceptable since there is plenty of information freely and widely available.[i] From time to time a specific data point may be lacking. But in these situations it is not just possible, but responsible and necessary, to make sense of missing data. Missing data is information, and information about which policy decisions can be made.

When it comes to maternal health[ii] policy, “lack of information” is additionally unacceptable because the information is there and the time for action is now. Whole generations of professionals encountering this “lack of information” in maternal health have dedicated their lives to both gathering information and making sense of missing data. Those dedicated researchers took the “lack of information” claim as an earnest assessment, and not “delay and denial” on the part of policymakers willfully blocking needed change to the status quo. But it is worth examining “lack of information” as both earnest, and as a pattern of delay or denial that has dire maternal health consequences.

"When researchers have analyzed maternal deaths and near-deaths to understand what went wrong, one element they have noted time and again is what some experts have dubbed “delay and denial” — the failure of doctors and nurses to recognize a woman’s distress signals and other worrisome symptoms, both during childbirth and the often risky period that follows."[iii] Though more removed from the clinical setting, delay and denial happens in policymaking too, and the consequences are just as dire. Lacking information is part of a dangerous pattern in perinatal health care.

Providers fail to listen to their patients, people who have critical information, and this leads to poor care. This was put starkly by Susan Goodhue when she told USA Today, “The staff, by not knowing, and not listening and not taking precautions, almost killed us.”[iv] Indeed, not listening guarantees a lack of information. It is worse for Black, Indigenous and other women of color, as Pat Loftman aptly described to ProPublica, “If you are a poor black woman, you don’t have access to quality OBGYN care, and if you are a wealthy black wom[a]n, like Serena Williams, you get providers who don’t listen to you when you say you can’t breathe,”[v] referring to Serena Williams’ high profile experience with providers who initially ignored her when she told them she was having a pulmonary embolism after giving birth.

As midwife Demetra Seriki points out in this 9News Interview, "Being heard is a life-saving conversation that every Black person needs to have with their provider. And if they’re not getting it with this provider they need to get it somewhere else."[vi] The same is true when it comes to policymaking, we can no longer countenance providers who fail to listen and then stand in the way of necessary change. The stakes are too high.

Whether it be the voice of patients, or experts, researchers, and advocates too much critical information is being dismissed by people in a position to save lives. “Failure to listen to Black women” is such a common problem across industries that it is Googleable, and it is unconscionable every time. Lacking information about maternal health, in this day and age, means you have either failed to make gathering information a priority, or you have dismissed certain information as illegitimate. The egregious inequities in perinatal outcomes by race alone should give you pause and make you look closely at how and to what extent you are contributing to those inequities; how and to what extent you are missing distress signals, how and to what extent your lack of information is part of the problem.

Lack of information has been a persistent excuse for obstetric racism both at the individual and structural levels from the beginning; it was designed that way. Individual distress signals are deligitimized among providers, and expert, researcher, and advocate distress signals are deligitimized among policymakers. Many, many people had information about obstetric racism before the information was prioritized or legitimized.[vii] This antipathy to information in maternal health has costs and must be urgently addressed.

The antidote is simple: make it a priority to gather information and listen more. Interrogate whether your lack of information is actually a failure to receive the available information; listening can be impeded by bias. It is part of the structure of white supremacy and other systems to categorize the voices of people of color, women, the queer, disabled, incarcerated etc, as illegitimate or not information. There is a long history of denying the information that Black and Indigenous people have (and need), denying the information that communities of color have (and need), denying the information that all kinds of marginalized people have (and need). “Lack of information” from people in power, when there is a cacophony of information being delegitimized, is a weapon of oppression.

Of course, it’s possible that when people say they lack information what they actually mean is that processing the information requires them to take a stand; perhaps a stand against white supremacy or some other powerful system. This too should give us pause. At whose expense and for whose benefit can you afford not to take a stand? At whose expense and for whose benefit can you afford not to listen? This is a good question in general and particularly acute when it comes to maternal health.

It is irresponsible to be in a policymaking position without the capacity to process information and the courage to take a stand. People who have been marginalized figure out how to process information and take the associated risks because they must as a matter of survival. Cede your power to them. Whether it is a lack of prioritization, a lack of legitimization, or a lack of willingness to take a stand, there is no excuse for showing up to influence policy without information. Come to the table ready or cede your power to those who are.

[i] Though there are other places to start, consider the 1925 White House Conference on Child Health and Protection that determined “untrained midwives approach, and trained midwives surpass, the record of physicians in normal deliveries.” See Judith Pence Rooks, Midwifery and Childbirth in America (Temple University Press 1997).

[ii] Using the term “maternal health” here, though the people who need health care for pregnancy and birth are not just moms, because there is a field of inquiry referred to in this way where there is a bounty of information.

[iii] Katherine Ellison and Nina Martin, "Severe Complications for Women During Childbirth Are Skyrocketing — and Could Often Be Prevented," ProPublica, December 22, 2017.

[iv] Alison Young and Alison Young, "Hospitals know how to protect mothers. They just aren’t doing it." USA Today, Jul. 26, 2018. See also this video: https://twitter.com/USATODAY/status/1022535120237080581

[v] Annie Waldman, "New York City Launches Initiative to Eliminate Racial Disparities in Maternal Death," ProPublica, July 30, 2018. Available at: https://www.propublica.org/article/new-york-city-launches-initiative-to-eliminate-racial-disparities-in-maternal-death And speaking of not breathing, see also Rachel Hardeman, et. al., "Stolen Breaths," N. Engl. J. Med. July 16, 2020. Available at: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp2021072

[vi] 9News.com, February 25, 2021. Available at: https://9news.com/embeds/video/73-33122767-fea2-44b7-a0aa-2ae9b40fd925/iframe?jwsource=cl

[vii] Not just in recent history, but for decades and decades and even hundreds of years. Every person whose reproduction has been politicized, through slavery or colonization just to name two broad examples, has information about inequities in health outcomes. The problem is not a lack of information but a characterization of some information as not information. There are so many citations for this, but to reinforce the point check out this Executive Summary from 2015.

Birth Equity Bill Package

We will post updates and fact sheets related to the birth equity bill package here!

We did it!! Our Birth Equity Bills passed!!

To protect human rights and address discrimination, mistreatment, harm, poor outcomes, and inequities in outcomes during the perinatal period -- Colorado passed three bills in the 2021 session.

1) Protection of Pregnant People in the Perinatal Period, SB 193 established basic human rights standards in perinatal care for all people, including those who are incarcerated.

2) Maternal Health Providers, SB 194 aligned perinatal care data and systems for equity.

3) Sunset Direct Entry Midwives, SB 101 continued the Direct-Entry Midwifery program.

Here is the summary of the final version of the bills as signed into law on July 6, 2021.

Here are the bills on the Colorado Legislature’s website: SB21-193 and SB21-194.

Experienced mistreatment in the perinatal period? Fill out this form, one of the new requirements of SB 193.

Here is a 45 minute video of a panel including with Representative Leslie Herod, Indra Lusero, Kayla Frawley, Demetra Seriki and Briana Simmons talking about the process (and made by Promise Venture Studios). And here is a shorter version of the video (12 minutes).

These bills are a part of our birth equity policy platform, which also includes the Direct-Entry Midwifery Sunset bill (we are keeping this page updated with info on the DEM bill). This is a community-based effort. Learn more about what that means in our “What is Community-Based” fact sheet, below.

ENDORSE the Birth Equity Bill Package as an individual or organization here, YOU can identify if you want to advocate, testify, share our social media tool kit once the bill is introduced on this form here. Our collection of logos from endorsing organizations is below.

ENGAGE NOW: you can write your law makers and committee members to vote yes on the bill! Using this template.

Fact Sheets:

Protección del periodo perinatal los derechos humanos son un resultado de la salud

Birth Equity Bills Content By Section

Birth Equity Bills Standards for Incarcerating Pregnant People

Answers to questions that came up in the Senate Hearing for SB21-194 on 4/14/2021

The Momnibus and Colorado’s Birth Equity Bill Package Side by Side

El Momnibus federal y la equidad de los nacimientos en Colorado

¿Qué significa “basado en la comunidad”?

Colorado as a part of National Efforts

This Colorado bill is part of a national effort to address inequity in maternal health through legislation like the Momnibus. And also aligns with this February 2021 publication, Diverse Colorado Voices: Community-Based Solutions for the Perinatal Period by Kayla Frawley, Holley Murphy, Lynn Vanderwielen. Sponsored by Clayton Early Learning, Families Forward Resource Center, and Raise Colorado, Caring for Colorado, Colorado Children’s Campaign, and Zero To Three.

Media about the Colorado Birth Equity Bill Package:

Colorado passes sweeping birth equity reform protecting the rights of pregnant people, Ms. Mayhem, August 27, 2021.

To end America's maternal mortality crisis, dismantle the racism that fuels it, CNN, July 14, 2021.

Elephants partly inspired these new Colorado laws, which aim to improve health care for pregnant people, Colorado Newsline, July 7, 2021.

Colorado Passes Landmark Birth Equity Bill Package, Harvard Law Bill of Health, June 22, 2021

Op-Ed: Meet the Leaders Behind Colorado’s Birth Equity Bill Package, Westword, June 12, 2021

Abortion Opponents Are Trying to Kill a Bill to Improve Maternal Health Care, Colorado Times Recorder, May 26, 2021

Colorado bill aims to protect incarcerated pregnant women’s rights, Denver Post, May 18, 2021

Colorado’s birth equity package aims to improve maternal mortality rates, Ms. Mayhem, May 7, 2021

Colorado bill aims to improve maternal health care, Associated Press, April 19th, 2021

Sen. Buckner: It’s time to pass legislation to improve maternal health outcomes in Colorado, April 18th, 2021

Colorado Birth Equity Bills Could Bring Better Maternity Care, Kayla Frawley, Westword, April 18th, 2021

Colorado bill aims to improve maternal health care, Associated Press & Durango Herald, April 14, 2021

New Bill Aims to Address Racial Inequities in Maternal and Infant Outcomes, Jordan Smith, Illuminate Blog, April 14th, 2021

Pregnant people of color face inequities, Dr. Jamila Perritt, Colorado Politics, April 12th, 2021

Approve Birth Equity Bills, Aubre Tompkins, CNM, Denver Post, April 11th, 2021

Outsources – Birth Justice with Indra Lusero: Learning histories and visioning for the future, Indra Lusero, March 29th, 2021

Why Colorado Needs to Pass the Birth Equity Bill Package, Kayla Frawley, Colorado Newsline, March 8th, 2021

Rep. Leslie Herod: Colorado to see maternal health legislation during the 2021 session, Colorado Sun, February 11th, 2021

Colorado Needs a Human Rights Approach to Maternity Care, Kayla Frawley in Colorado Newsline, February 11th, 2021

Other timely, related media:

Leading maternal health experts advocate for Medicaid extension to 12 months postpartum in Scientific American here.

The U.S. Maternity Care Consent Problem, Ms. Magazine, February 2021

Op-Ed about the death of Elijah McClain by Bill Sponsor Senator Janet Buckner and Senator Rhonda Fields, March 2021

9News feature of Colorado midwife Demetra Seriki, and this profile of her by the Colorado Trust

New York Times, March 11, 2021, Why Black Women Are Rejecting Hospitals in Search of Better Births

Slate, March 9, 2021, I’m an Obstetrician. Stop Stigmatizing Home Births.

Elephant Circle articulated some of the elements of the Birth Equity Bill along with other maternity care experts in a response to CMS Office of Minority Health request for information about improving rural maternal and infant health care here.

Why Is It So Risky to be a Black Mother, Colorado Trust

Related Events:

A recording can be found here of the first hearing for 194 on Wednesday, April 14th at 1:30pm Mountain (in the Senate Health Committee). SB 194 starts at 1:35:40

A recording can be found here for the first hearing for 193 on Thursday, April 22nd at 1:30pm Mountain (in the Senate Judiciary Committee). SB 193 starts at 2:11:30.

BIRTH Equity Lobby Day! Meet with your legislators and hear about how a bill becomes a law. March 31st, Register here.

Community Meeting February 27, 2021, recording and pdf of slides about the bills in detail, and pdf of slides about the criminal justice sections.

Check out our events page for more.

Direct Entry Midwives Sunset 2021

Get updates and facts sheets about the 2021 DEM Sunset process here!

We will be posting updates and fact sheets here about SB21-101 so folks who are interested can access, advocate and be informed!

Here is our proposed amendment to change the legislative references from register to license.

Fact Sheets:

Professions Licensed in Colorado

2000 DORA report for DEM Sunset - just the pages about licensed v. registered

Report to DORA - 2020:

Full Report to DORA from Elephant Circle, March 2020

Other:

EC letter in response to the CMA

Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies, Report and Recommendations of the Direct-Entry Midwife Risk Management Working Group: Pursuant to §12-37-109(3)(b)(I), C.R.S., October 1, 2016. Plus our fact sheet on Colorado numbers and liability in general from 2016, and our fact sheet for the working group in 2016.

Letter of support from Families Forward Resource Center

Letter of support from a local midwife

Letter from Southern Cross Insurance

Support Letter from Dr. Seefeldt

Webinars:

Here are slides from the webinar with the Colorado Midwives Association on March 19, 2021: CMA slides on licensure, EC slides on Malpractice. And here is the recording.

History of Midwifery Laws in Colorado

Details about the history of midwifery laws in Colorado since the early 1900s.

The latest bill in Colorado’s midwifery history was introduced last week, and the dynamics were much as they have been for 100 years - since doctors began the campaign to eliminate midwifery. Here’s a great video on the “culture war between doctors and midwives,” though I think that is a generous way of putting it. I also recommend, Judith Pence Rooks, Midwifery and Childbirth in America, (Temple University Press 1997) and Judy Barrett Litoff, The American Midwife Debate: A Sourcebook on its Modern Origins, 5-7 Greenwood Press (1986).

Here is a short video I made about the history of midwifery laws in Colorado specifically. This blog post provides the details behind that video. In Colorado, the campaign to eliminate midwifery didn’t seem to culminate until 1941 when Senate Bill 640 proposed a revision to the Medical Practice Act that would end midwifery licenses with the goal of eliminating midwifery completely. Patricia G. Tjaden, “Midwifery in Colorado: A Case Study of the Politics of Professionalization,” 10 Qualitative Sociology, 33 (1987). The law was passed with a grandmothering provision that allowed already licensed midwives to practice but no new midwives to take their place.

In the 1940s most births were taking place at home, but by 1955 ninety-nine percent were in the hospital. Marian McDorman et. al., Trends and Characteristics of Home and Other Out-of-Hospital Births in the United States, 1990-2006, 58 National Vital Statistics Report 11 (2010).

In 1976 the Colorado legislature erased the history of midwifery from the Medical Practice Act, deleting the section on midwifery licensure and all references to it. H.B. 1032, 50th Gen. Assemb.. 2nd Sess. (Co. 1976). But midwifery had not disappeared in Colorado, it just moved underground, and along with it, homebirth.

My brother was born at home in Longmont, Colorado, 1977; his birth is one of my earliest memories and 1977 is the same year that Certified Nurse Midwives were licensed here. H.B. 1526, 51st Gen. Assemb, Reg. Sess. (Co 1977) . That law amended the Medical Practice Act and created a licensing scheme for advance practice nurses trained in midwifery, under the Board of Nursing.

In 1982, the same year my youngest sister was born at home in Boulder County, Karen Cheney a Boulder County midwife and founding member of the Colorado Midwives Association, was charged with the crime of practicing medicine without a license.

In response, House Bill 1528 “Concerning Midwifery,” carried by a state representative from Boulder was introduced in 1983. The bill proposed an Advisory Board under the Colorado Department of Health to regulate midwifery, defined midwifery as not the the practice of medicine, and included a provision stating that parents have the right to decide how they give birth. H.B. 1528, 57th Gen. Assemb, Reg. Sess. (Co 1983). The House Health, Environment, Welfare and Institutions Committee held a hearing on March 23, 1983 that 150 people attended. Medical professionals including nurses, doctors and nurse midwives spoke in opposition to the bill, as they do.